IN DECEMBER 1917, Halifax, Nova Scotia, was the hub of the Dominion of Canada. World War I had brought activity and prosperity to the port. The harbour was crowded with wartime shipping. Convoys of ships loaded with war supplies of food, munitions and troops gathered in Bedford Basin ready for the voyage to Europe with heavily-armed warships as escorts. Neutral vessels anchored in the harbour, their crews forbidden to land for fear any might supply information to the enemy. New railway lines and terminals were almost completed, made necessary to carry the extra traffic handled by the staff of the Intercolonial Railway. The population was swollen with troops, some awaiting embarkation for Europe, some garrisoned there, their families, and people who had come to benefit from the plentiful employment.

Devastated house, north section of Duffus Street, Halifax

Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, Charles A. Vaughan Collection, N-14,024

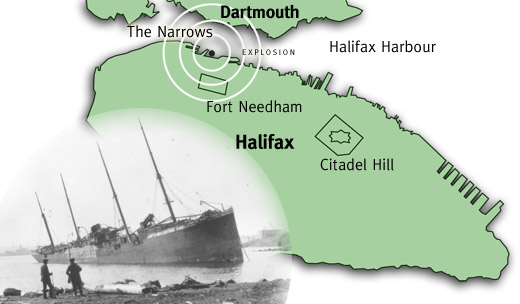

At 7.30 a.m. on December 6, the French ship Mont-Blanc left her anchorage outside the mouth of the harbour to join a convoy gathering in Bedford Basin. She was loaded with 2,300 tons of wet and dry picric acid, 200 tons of TNT, 10 tons of gun cotton and 35 tons of benzol: a highly explosive mixture. At the same time the Norwegian vessel Imo, in ballast, set off from the Basin bound for New York to pick up a cargo of relief supplies for Belgium. At the entrance to the Narrows, after a series of ill-judged manoeuvres, the Imo struck the Mont-Blanc on the bow. Although the collision was not severe, fire immediately broke out on board the Mont-Blanc. The captain, pilot and crew, expecting the ship to blow up immediately, launched the lifeboats and took refuge on the Dartmouth shore.

IMO on the Dartmouth Shore

MMA MP 207.1.184/270 (photograph only)

The ship burned for twenty minutes, drifting until it rested against Pier 6, in the Richmond district, the busy, industrial north end of Halifax. The spectacle was thrilling, and drew crowds of spectators, unaware of the danger. Only a handful of naval officers and a railway dispatcher had learned of Mont-Blanc's explosive cargo and there was little time to spread a warning.

Explosion

Just before 9.05 a.m., the Mont-Blanc exploded. Not one piece of her remained beside the dock where she had finished her voyage. Fragments rained on the surrounding area, crashing through buildings with enough force to embed them where they landed.

Clock found in explosion wreckage

Artifact: NSM #Z3887, Photo: MMA, N-15,066

Churches, houses, schools, factories, docks and ships were destroyed in the swath of the blast. Children who had stopped on their way to school, workmen lining the windows, families in their homes, sailors in their ships, died instantly. Injuries were frightful, blindness from the splintering glass adding to the shock and bewilderment. The captain, pilot and five Imo crew members were killed. All from the Mont-Blanc survived, apart from one man who later died from his wounds.

The Silliker Car Works

MMA, Charles A. Vaughan Collection, N-14,014

Rescue

Mercifully, rescue began quickly, with the thousands of well-disciplined troops and naval strength available. City officials speedily arranged for volunteer help: relief committees had been formed by the afternoon of the disaster. Word went out to the surrounding areas and they responded with commendable speed. Hospitals and places of shelter were soon overcrowded. All possible buildings-even ships in the harbour-were commandeered, and some of the injured and homeless sent by rail to other cities.

YMCA Emergency Hospital

MMA Kitz Collection, N-14,014

News of the disaster reached Boston the same morning. That very night a train loaded with supplies, together with medical personnel and members of the Public Safety Committee, left for Halifax. Help poured in from all over Canada and many parts of the world, with the continuing generosity of Massachusetts unforgettable. Each Christmas the huge tree that glitters on Boston Common is a thank-you gift from the people of Nova Scotia.

1,630 homes were completely destroyed, many by fires that quickly spread following the explosion; 12,000 houses were damaged; 6,000 people were left without shelter. Hardly a pane of glass in Halifax and Dartmouth was left intact.

The death toll rose to just over 1,900. About 250 bodies were never identified; many victims were never found. Twenty-five limbs had to be amputated; more than 250 eyes had to be removed; 37 people were left completely blind. Hospitals treated well over 4,000 cases, and private doctors hundreds more.

Temporary Housing Supplied by Massachusetts Relief

MMA Charles A. Vaughan Collection, N-14,174 and N-14,127

The Dominion Government appointed the Halifax Relief Commission on January 22, 1918. It handled pensions, claims for loss and damage, rehousing and the rehabilitation of explosion victims. It was disbanded only in June, 1976. Pensions are now paid by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Result

As a result of the tragedy certain benefits accrued to the city. Medical treatment, social welfare, public health and hospital facilities increased and improved. Regulations relating to the harbour were tightened, making it as safe as human errors of judgment would permit. The Hydrostone development, built as relief housing, still stands, an early example of a very high standard of urban development.

Hennessey and Kane Places, Hydrostone Development Temporary Housing Supplied by Massachusetts Relief

MMA Charles A. Vaughan Collection, N-14,174 and N-14,127

The official enquiry opened less than a week after the explosion. The captain and pilot of the Mont-Blanc and the naval commanding officer were charged with manslaughter and released on bail. Later the charges were dropped, because gross negligence causing death could not be proved against any one of them. In the Nova Scotia District of the Exchequer Court of Canada in April, 1918, the Mont-Blanc was declared solely to blame for the disaster. In May, 1919, on appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada, both ships were judged equally at fault. The Privy Council in London, at that time the ultimate authority, agreed with the Supreme Court's verdict.

Thus no blame was ever laid in the largest man-made explosion until the atomic age, when its effects were studied by Oppenheimer in calculating the strength of the bombs for Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Memorial at Fort Needham, Halifax

Photo courtesy of Dennis Jarvis © All Rights Reserved

Many gravestones, artifacts and monuments in the cities of Halifax and Dartmouth are reminders of the explosion. The most impressive is the Memorial Bell Tower on Fort Needham, overlooking the explosion site. Hanging there is a carillon of bells, donated in 1920 to the United Memorial Church, which was built to replace two churches destroyed in the explosion. The presentation was made by a young girl who had lost her entire family in the blast, her mother, father and four brothers and sisters. At 9 a.m. on December 6, every year, a service is held there in memory of the victims of the Explosion. The bells ring out and can be heard across the Narrows in north Dartmouth, all around Fort Needham, and in the areas devastated by the Halifax Explosion of 1917.

References

- Armstrong, John Griffith. The Halifax Explosion and the Royal Canadian Navy (2002). A recent examination of the impact of the Explosion on Canada's Navy.

- Bird, Michael J. The Town that Died. (1962). A brief but concise account of the event, based on interviews with some of the survivors and naval records. Reprinted many times.

- Flemming, David B. Explosion in Halifax Harbour: The Illustrated Account of a Disaster that Shook the World (2004). A fully illustrated account of the explosion.

- Kitz, Janet F.

- Shattered City: The Halifax Explosion and the Road to Recovery. (1989). The most comprehensive account available.

- Survivors (1992). The explosion through the eyes of children who survived.

- Mahar, James & Rowena Too Many to Mourn (1998) The explosion reconstructed from the experience of a devastated family in the most affected neighbourhood.

- Metson, Graham. The Halifax Explosion. (1978). A work containing copies of original documents and many never-before-published photographs. It also includes Archibald MacMechan's excellent first-hand account.

- Ruffman, Alan & Colin Howell eds, Ground Zero. (1994) An illustrated collection of articles examining historical, cultural and scientific aspects to the explosion.

Written by Janet F. Kitz

You may reproduce this information for personal and study purposes only. Certain images copyright their respective owners. Please credit The Nova Scotia Museum, Department of Tourism, Culture and Heritage. Images or text not to be reproduced for commercial purposes without permission from the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic. Contact webmaster with questions or comments regarding this page.

Created March 29, 2000. Last Revised 19 Feb 2009 - TF.