As the twentieth century dawned, many felt marine tragedies were a thing of the past. Science promised solutions to everything, from poverty to disasters. The engineering marvels of the age were steamships. Steel hulls, turbines and electricity enabled ships to quadruple in size in the ten years before 1912.

Fighting to exploit increased immigration, business and leisure travel were rival steamship lines: the Cunard Line (originally founded by Samuel Cunard from Halifax) and the White Star Line. When Cunard launched the giant Mauretania in 1907, White Star Line, responded with plans for two of the largest steamships in the world, Olympic and Titanic.

Titanic was launched on May 31, 1911. Building on lessons from Olympic, she was an extra thousand tons and carried a hundred more passengers. For her brief career, she was the largest ship in the world, in fact the largest moving object ever created. Larger ocean liners were built after Titanic, but few ever matched her legendary reputation for lavish craftsmanship. Titanic's seven decks provided the facilities of a medium-sized city, from post office to sidewalk cafés. Three passenger classes were rigidly segregated by locked barriers, ranging from the lavish decoration and country club facilities in First to the bare painted steel, low ceilings and naked light bulbs in Third.

Titanic left Southampton on April 10, 1912, stopping briefly in Cherbourg, France and Queenstown (now Cobh), Ireland. She was due in New York on April 17.

Credit: Titanic's 1st class staircase closely resembled Olympic's, shown here in the Museum's exhibit.

US Library of Congress US Z62-26812

Sinking

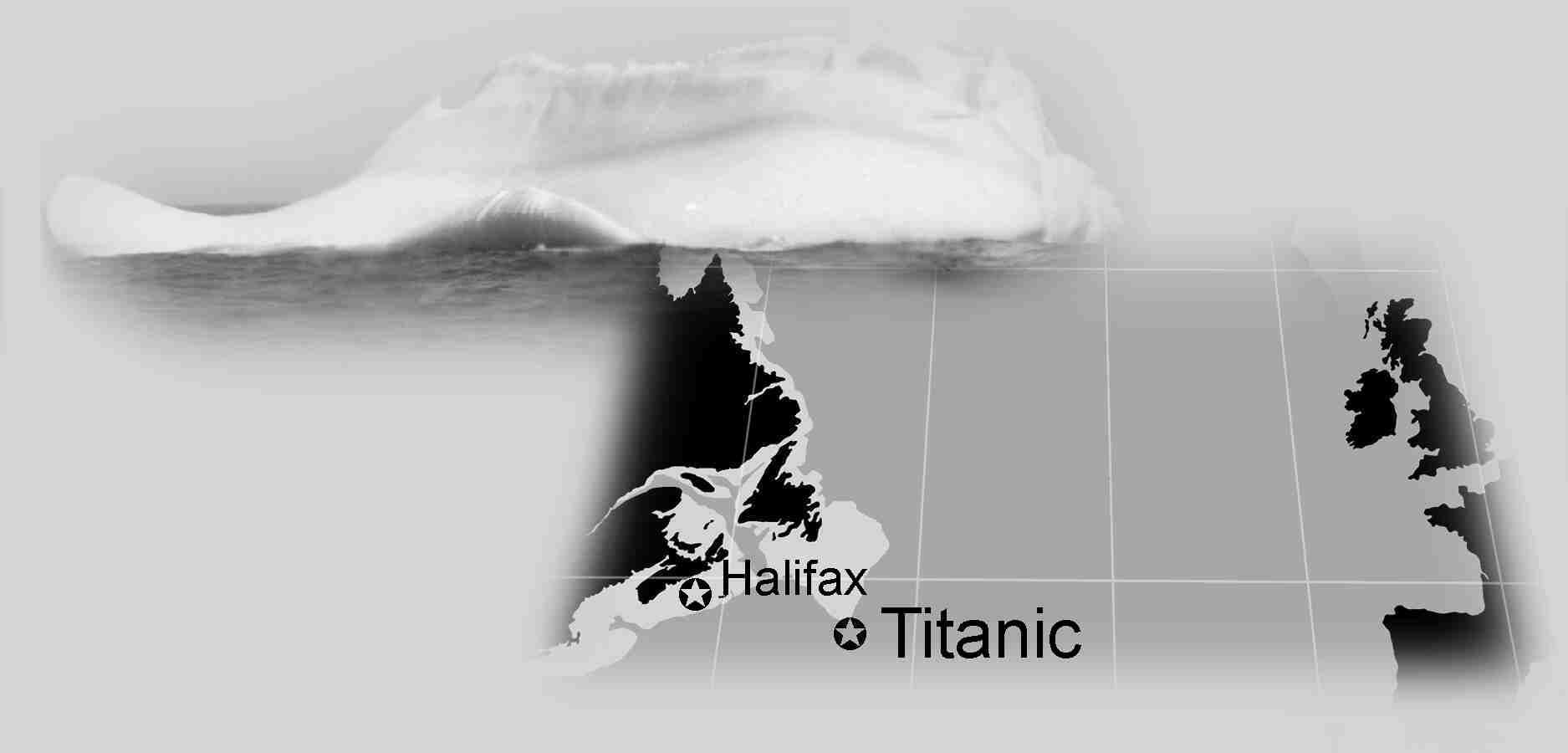

Despite numerous ice warnings, Titanic steamed full speed into a massive field of icebergs. She struck one at 11:50 pm, April 14 and sank two hours and forty minutes later. Her reported position, 41 46 Lat. 50 14 Long., was 700 nautical miles east of Halifax. There were over 2200 people aboard Titanic. Only 705 survived. In the first few hours of confusion, officials in New York believed that a damaged Titanic would come to Halifax, the closest major port. Special trains were on the way with relatives and immigration officials, when the news broke. Titanic was gone forever. The Cunard liner Carpathia was taking survivors to New York. The dead would come to Halifax.

Credit: It is impossible to identify the precise iceberg that sank Titanic but Minia's crew believed this one, photographed near bodies and wreckage, was responsible.

Samuel Prince Photograph Collection, Courtesy of Alan Ruffman

Recovery

The strategic position of Halifax made it the base for cable ships which repaired breaks in the underwater telegraph cables connecting Europe and North America. The White Star Line turned to these ships to search for bodies. Their tough crews, used to working in rough seas and ice, were ideally suited for the grim task.

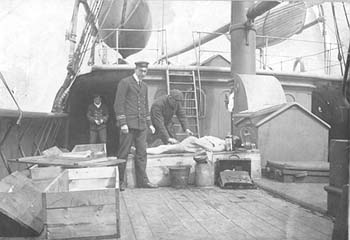

Credit: A boat crew from the Cable Ship Minia picks up one of the Titanic victims. Recovery was hard, grim work, amidst large waves and dangerous ice floes. Crews were paid double and given extra rum rations.

MMA, M2009.74.1

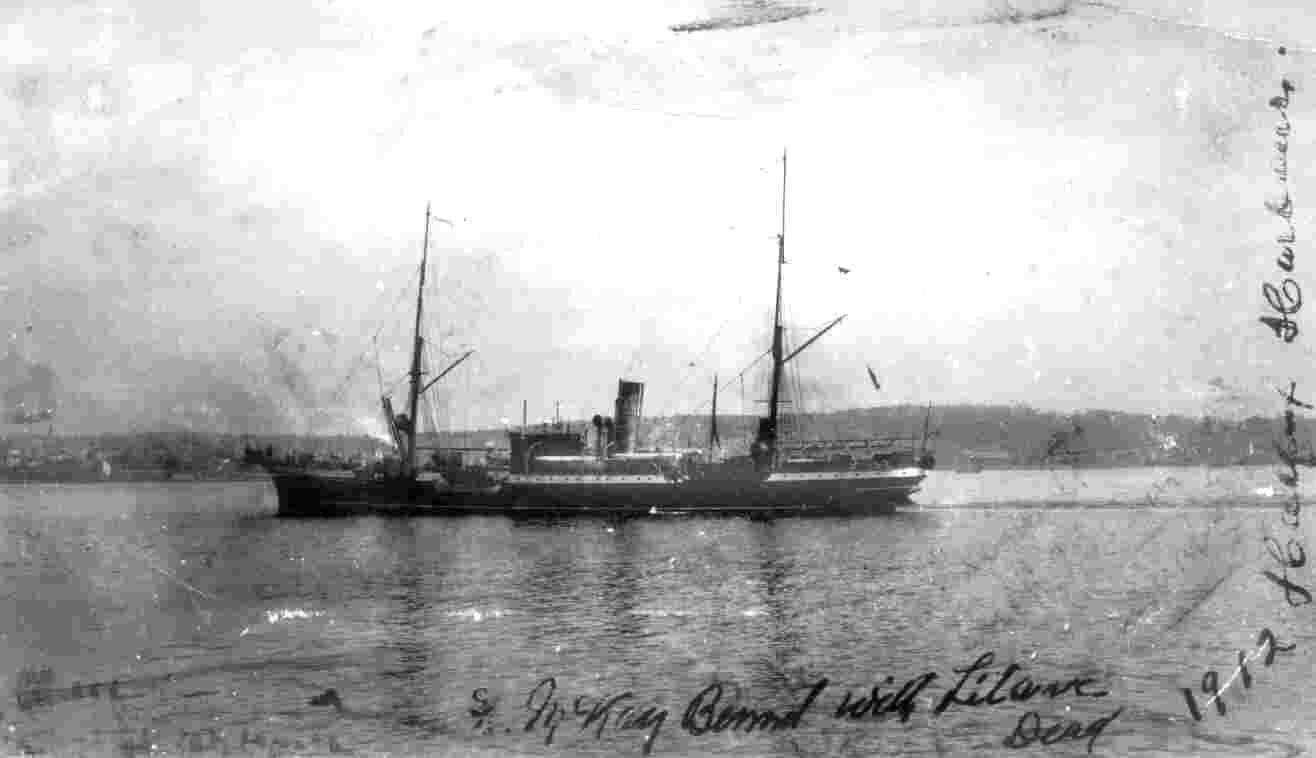

Before the survivors even arrived in New York, the first cable ship left Halifax to search for bodies. With coffins, a 100 tons of ice, an undertaker and a chaplain, Mackay-Bennett left on April 17, arriving on-site three days later. She found 306 bodies, so many that embalming fluid ran out and 116 had to be buried at sea. Another cable ship, Minia, departed Halifax on April 22, relieving Mackay-Bennett and finding another 17 bodies. The Canadian Government lighthouse supply ship Montmagny left Halifax on May 6, and found four bodies. A Newfoundland sealing vessel, Algerine, sailed on May 16 but found only one body, steward James McGrady, the last to be recovered. In total, 328 bodies were found. Twelve hundred were never recovered, some sinking with Titanic, others being dispersed by currents, bad weather and ice.

Credit: A Titanic victim is embalmed aboard the cable ship Minia.

Nova Scotia Archives and Records Management, N-715

Nova Scotia was no stranger to White Star Line shipwrecks, as the SS Atlantic sank near Halifax in 1873 taking over 500 lives. For the 209 Titanic bodies that came to Halifax, the Deputy Registrar of Deaths, John Henry Barnstead improvised a remarkable identification system. Bodies were numbered as they were pulled from the sea and personal effects were bagged. Further details (tattoos, clothes, jewellery) were noted and photographs taken at the temporary morgue in the Mayflower Curling Rink.

Credit: With flags at half mast and coffins stacked on the stern, Mackay-Bennett arrived in Halifax to the tolling of church bells on 30 April 1912.

M.M.A., MP 29.3.1

Identification

Barnstead's system proved invaluable after a much larger disaster in 1917 when it was used to handle and identify the 2000 victims of the Halifax Explosion. Even later, in 1992, Barnstead's meticulous records allowed researchers to put names on six previously unidentified Titanic graves.

Credit: Titanic victims are landed from Minia at the Naval Dockyard in Halifax.

MMA, M2009.74.2

Fifty-nine bodies were shipped home to relatives, but a hundred and fifty were buried in three Halifax cemeteries: 121 graves at Fairview Lawn (nondenominational), 19 graves at Mount Olivet (Catholic) and ten graves at Baron de Hirsch (Jewish). The victims range from the Presidential Secretary of the White Star Line to orchestra members and coal stokers. About a third are unidentified. One of the first victims to be buried was a small, unidentified boy, carried to his grave at Fairview by Mackay-Bennett's crew.

Lessons Learned

Lifeboat Reform

Most people aboard Titanic were doomed because her lifeboats could carry only half of those aboard. After Titanic, additional boats were immediately installed on North Atlantic steamships. Within a year international regulations required lifeboats for everyone and regular drills.

The Role of Wireless

Investigations revealed that heavy commercial wireless traffic had taken priority over ice warnings. Some exhausted wireless operators were off duty and asleep when Titanic called. New regulations required a continuous watch for distress calls. They also called for automatic alarms, to be triggered by distress calls.

International Ice Patrol

Before Titanic, ships depended on seasonal ice predictions and occasional reports from other ships. These were often dismissed. After Titanic, an international ice patrol was established to track ice movements, issue warnings and research ice conditions. It continues, now using satellites.

Credit: Titanic Graves Fairview Lawn Cemetery

M.M.A., N-6812

Discovery

Lying 3.8 kilometres underwater, Titanic's wreck remained mysterious and undisturbed until 1985 when it was discovered by a French and American expedition. Important scientific studies of Titanic's wreck have been led by Canadian scientists at the Bedford Institute of Oceanography in Halifax. They include the first tests of Titanic's steel plating and pioneer studies of the iron drippings called "rusticles" that cover her wreck.

Titanic's wreck has also attracted salvagers who have picked over the wreck for commercial display. Most marine museums are opposed. They consider Titanic to be a memorial and archeological site requiring minimal intervention, systematic mapping and sharing of research for scrutiny by archeologists and scientists.

Credit: Titanic deckchair, recovered by Minia and given to Rev. Henry W. Cunningham for his work performing memorial services and burials at sea.

M.M.A., N-18,803

Titanic and Popular Culture

Titanic instantly became a landmark in popular culture. Within weeks of her loss, films, books and countless musical pieces were produced and an entire industry still thrives around Titanic. Interest has ebbed and flowed over the decades as each generation finds new meanings in the Titanic tragedy.

Credit: "Instant" Titanic Book published by Logan Marshall in 1912.

Courtesy Jay White

References

Brown, Richard. Voyage of the Iceberg, (1983). The sinking from the iceberg's point of view, written by a Canadian scientist exploring the natural and human history of the disaster.

Eaton, John and Charles Haas. Titanic: Triumph and Tragedy (2nd Edition, 1997). An exhaustive account, including a detailed chapter on the role of Halifax.

Lord, Walter. A Night to Remember (1955) The classic minute by minute account of the disaster.

Lynch, Don and Ken Marschall. Titanic: An Illustrated History (1992 ) A beautifully illustrated and detailed portrait of Titanic.

Ruffman, Alan, Titanic the Unsinkable Ship and Halifax (1999) The most authoritative account of Halifax's role, beautifully illustrated by the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic's collection.

More Titanic sources and Links on the Museum's Titanic Research Page.